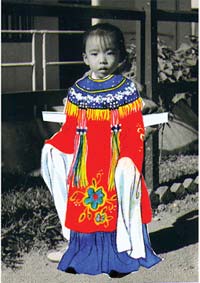

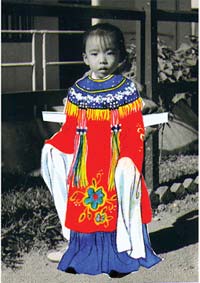

Mary Sui Yee Wong, Mei Ren, 2008. Participatory sculpture installation: photographs and wood, dimensions variable.

Marie Madelaine Péron

MP: While preparing for this interview, I could not help but wonder how you began your artistic practice. At the age of thirty, what prompted you to move away from Vancouver and leave employment in the medical research field to pursue studies in the fine arts at Concordia University?

MW: Being an artist is something that I’ve always thought about, not necessarily a visual artist but let’s just say that the creative process was always a part of my life from a very young age. I remember being very excited when I first learned how to draw and make things. All throughout high school and university I had studied art, but I never pursued it fully because it wasn’t something that was sanctioned by my parents.

By the time I was about thirty, I was going through a bit of an identity crisis. Was I going to continue working in medicine? I had reached a certain point in my career where I couldn’t do the work I was doing without further study. So, I was either going to go back to school and bone up my chemistry and study medicine or I would study art. I hated chemistry and I loved to draw; that was the deciding factor.

I never planned on becoming a practicing artist. At that time, I wanted to do something in life that could make me happy. I had worked for ten years, so I had a bit of financial stability, and I decided I would give myself the luxury of doing something I could lose myself in. So I decided that I’d go back to school and study art, not necessarily with the intent of becoming a practicing artist. I just wanted to make things and have some kind of outlet for my creative expression.

MP: You have worked with curator Alice Ming Wai Jim in the past. What was your reaction when she asked you to participate in Rearranging Desires?

MW: Well, we had several interesting conversations when Alice was invited to curate this show. The idea of curating an exhibition of Chinese or Asian Canadian Concordia Alumni can be an oddity. There are particular socio-political and cultural implications to this kind of positioning that raises important questions of context and content. When speaking with Alice, we talked about the various strategies available to us. The challenge was to come up with a project that would be self-reflexive and critical of the very thing that one chooses to become part of, in order to move conversations in new directions.

MP: Could you tell us about your works Mei Ren and Yellow Apparel?

MW: Yellow Apparel is sort of an extension of an earlier work that I had created during my M.F.A. It started out as an ironic joke. About fifteen years ago, I found this fabric that had these strange prints on it which I thought were completely wacko. I bought whatever was left of this fabric, which was all of maybe eight yards on a little pole because I thought that it was too good leave this on the shelf for anyone else to have.

Back then I couldn’t find the right way to work with that material without it being too “in your face.” So I hung on to the fabric waiting for the right opportunity to use it. During grad school, there were a couple of other students who had formed this group called the Postcolonial English Society and were doing performances, and I decided to make costumes for them out of my found fabric. That’s how it all started.

Unlike the 80’s, conversations about identity were different in the new millennium. I felt there was actually more tolerance and my work could be more ironic and cynical, but with humour.

In my first exhibition of Yellow Apparel, several of my garments were stolen and my intentions of working with faux fashion as a way to explore the complexities of globalization and acculturation were arrested. I couldn’t continue making anymore garments because the fabric was no longer being manufactured. So, I turned to other mediums such as photography, mass produced postcards and newspaper ads as a natural extension of my idea. I had always intended to revive the garments as object and Rearranging Desires gave me the perfect opportunity to do this. In collaboration with a New York designer, I had the fabric scanned and reproduced so that I could create a new line of garments.

In conjunction with Yellow Apparel, the second piece in the exhibition is entitled Mei Ren, 美人 (mei 美 means beautiful and ren 人 means person in Chinese). In this work I wanted to draw from personal memories to address identity. I chose an old photo of myself that was taken when I was living in Hong Kong. When the picture was taken I was 100% Chinese, in the full sense of the term: I was living in Hong Kong and was only speaking Chinese. Yet the picture doesn’t really indicate this reality in any way shape or form. So, in an effort to address these issues surrounding my Chineseness, I am having a life-size cut out of myself made into a maquette. Accompanying the doll will be a series of authentic and traditional clothing from different regions in China that are inspired by a paper-cut series illustrated by a non-Chinese person for a book by Barbara Steadman called Chinese Girl and Boy Paper Dolls (New York: Dover, 1996). The costumes were from Shananxi, Beijing, Qinghai, Liaoning, Quizhou, and Guangxi-Zhuang. This work is intended to play with notions of national identity and homeland. All of the outfits are obviously ethnic but they are not obviously Chinese.

MP: You seem to gravitate towards mediums that can be touched, felt, or that occupy literal space. How important are these tactile or spatial elements to your work?

MW: Very. It is absolutely essential to the work that I am doing. When I decided to become an artist it wasn’t just about getting my ideas out there. Perhaps it’s due to my opera background, while my spatial interest is probably due to my dance background, but the relationship between different materials and form is tantamount to my concern. Materials and form are deeply embedded with meaning and can tell a lot about one’s history and one’s heritage. One of the most important things for me is to identify materials that allow for a relationship between me as a Chinese-Canadian and my personal history. In consciously choosing to work with materials that function as cultural markers, I also seek to create common ground that open up conversations to allow others to share their personal experiences.

MP: Do you have a favourite work in your portfolio, or a work that you hold especially close to heart?

MW: Yes, I do. I have a couple. It’s interesting because they are not fully developed at this point. I really loved the work that I did when I first started out in the undergrad program. At this time, I was simply taking the material and altering its identity by changing its colour. It’s not a work that I show very often in public. I think I’ve shown my rice-work only once because I received an enormous amount of critique for using food substance as an artistic material. Now, using rice as a medium is probably equally charged because of the price of rice and food (that has drastically increased).

MP: As a contemporary artist today, how do you find a balance between work that you have been asked or commissioned to do, and work that is true to your heart?

MW: In general, I have to say that I’ve been very lucky. I consider myself fortunate because my work is exhibited in the mainstream, and people know it for what it is, despite the decline in popularity of identity politics. I’ve never felt that I had to compromise what I wanted to say. It is very important to my practice that I am able to make meaningful work and that there is continuity between pieces. I don’t seek opportunities which don’t allow that to happen.

MP: Is there a question or a topic that you would like to be asked about in an interview that no interviewer seems to ask?

MW: Depending on who was driving the conversation, I find it very rare that I don’t get to say what I want to say. There have been times though when I thought it was curious why, whenever I am asked about my work, it was about the issues relating to identity as opposed to the form. But you did address the tactility and that gave me the opportunity to talk about it. It’s one of those things that tends to happen when an artist is categorized – they are asked very specific questions in relationship to that categorization.

September 20, 2008

Mary Sui Yee Wong, Mei Ren, 2008. Participatory sculpture installation: photographs and wood, dimensions variable.

Links suggested by Mary Sui Yee Wong:

Paper doll cut outs

http://search.store.yahoo.net/cgi-bin/nsearch?catalog=doverpublications&query=chinese%20dolls

http://store.doverpublications.com/by-subject-children-dover-little-activity-books-cut-out-paper-dolls.html

Yellow Peril

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yellow_peril

Josephine Siao (Shirley Temple of Hong Kong)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nk_gRudm6ug&eurl=http://widget.slide.com/version/20080924173529/widgets/ytWrapper.swf?playerUrl=http://www.youtube.com/apiplayer&proxyId=proxy_0_42178998002782464&wrapperId=wrapper_0_15438578044995666&videoId=nk_gRudm6ug

Mary Sui Yee Wong is a multidisciplinary artist who immigrated to Canada from Hong Kong, with her parents in 1963. She obtained an MFA in Fibres in 2003 from Concordia University, where she was Assistant Professor in Studio Arts until 2008. From 2002 to 2005, Wong coordinated Concordia's MFA & Studio Arts Visiting Artist Programs. Her work has been shown extensively in exhibitions including: a lullaby, Seoshin Gallery (Jeonju, South Korea, 2003); La Demeure, Optica Gallery (Montreal, 2002); Dust on the Road, MAI – Montréal, arts intercultural) (Montreal, 2001) and Round House (Vancouver, 2002); Nature Morte, Jardin de Chine du Jardin botanique de Montréal (1999); Travel Diary, Kunming, New York, Montreal, Observatoire 4 (Montreal, 1998); The Cage Maker, Helen Pitt Gallery (Vancouver, 1997); Well Wishers II, McCord Museum (Montreal, 1996); Other Real Stories, Fotofeis (Scotland, 1995); Within the Shadow of the Sun, York Quay Gallery (Toronto, 1993); and Self Not Whole, Chinese Cultural Centre (Vancouver, 1991). Wong has been involved in numerous curatorial initiatives, including: Resistence, Diagonale, Centre des textiles et des fibres (Montreal, 2007); Chez Soi/Home, MAI – Montréal, arts intercultural (Montreal, 2004); Autumn Melodies: A Centenary Celebration of Master Cheng Yan Qui, Todmodern Mill Heritage Museum (Toronto, 2004); forgotten spaces, Bain St-Michel (Montreal, 2003); From the Heart, La Chapelle Historique du Bon Pastor (Montreal, 2000); (be)longing, Optica Gallery (Montreal, 1997); The Secrets of Cantonese Opera, McCord Museum (Montreal, 1996); and Un Coup D’Oeil sur l’Opéra de Pékin, La Maison de la Culture Frontenac (Montreal, 1994). Wong is an active member of the arts community as President of the Little Pear Garden Collective, past board member at Optica Gallery, Articule Gallery and honorary member of the Yuet Sing Operatic Society.

Marie Madelaine Péron is currently an MA student in Art History at Concordia University. Her research interests are in contemporary aboriginal and indigenous art and curating national collections.